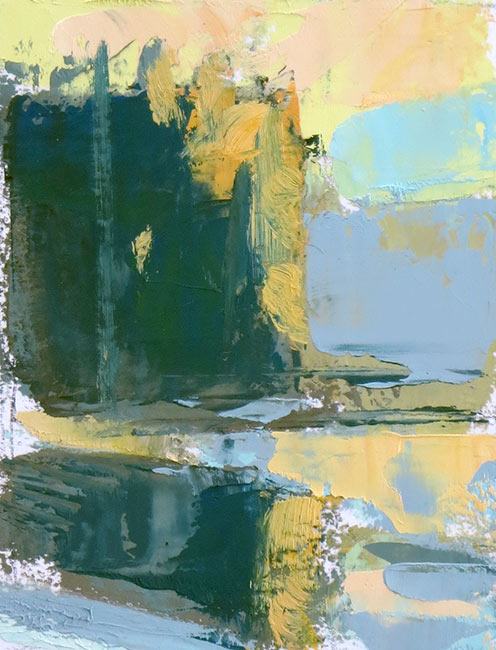

Mitchell Albala, Reflections on a Deep Pond, oil on paper, 4″ x 3″

This past summer I was invited to do a painting demonstration at Winslow Art Center‘s plein air event. After the morning painting sessions, several of the guest instructors gathered for an impromptu Q & A session. One of the questions posed was, “What guides your color choices?” A deep and complex topic, to be sure!

I talked about identifying the color groups within the scene. Another instructor said she pays a lot of attention to the balance between cool and warm colors. Another painter said he is guided largely by an intuitive response to color. Feeling. That struck me as a very evolved place from which to make color choices. So it got me to thinking … What are the stages we go through in learning to interpret color? We aspire to make intuitive color choices, but does the more experience we have with color theory help us do that?

I see our color development as being divided into three stages. Of course, there is some overlap between the stages, but for the most part, I believe that each stage offers important lessons about color that help us evolve into the next stage.

Stage 1 – Painting the colors we see

We all start learning about color by trying to paint the colors we see. This is often referred to as observational color. Here we are concerned with the color of something as it appears to our eye, under the influence of a particular color of light. We see a color and try to accurately record its value, hue, temperature and relative intensity. This teaches us a great deal about the properties of color and how to control them. It teaches us how to mix colors that can produce the effects we are after, and how the colors of the landscape translate into paint.

Working with observational color may be the first stage, but it is not a baby step. It covers all the essential theory that is necessary to create effective representational landscapes. Also see The Gifts of Plein Air – Living Color through Direct Observation and Ways of Interpreting Landscape Color: In the Studio vs. Plein Air.

Wonderful paintings can be produced with the skills we learn in Phase 1. And we continue to develop these skills even as our understanding of color evolves.

Perhaps the most profound realization of Stage 1 is that replicating the colors we see is not entirely possible (which seemingly contradicts the premise of observational color). Pigments on paper or canvas are incapable of expressing the range of brilliance and luminosity generated by natural light. No matter how intense we make our colors, or how strongly we may render their value contrasts, our pigments can never compete with the brilliance of natural light. To achieve the effects we want, we must be willing to alter and modify the colors we see — and that’s when we transition into Stage 2.

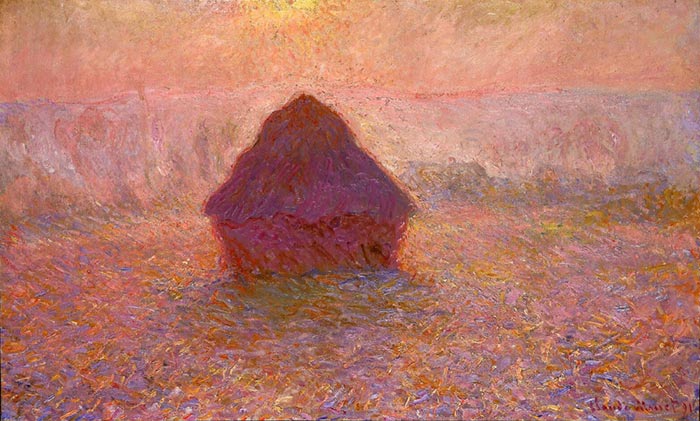

Claude Monet, 1891, Haystacks, Sun in the Mist. The Impressionists are widely regarded as masters of observational color. Monet is famously quoted as saying:

Claude Monet, 1891, Haystacks, Sun in the Mist. The Impressionists are widely regarded as masters of observational color. Monet is famously quoted as saying:

“Try to forget what objects you have before you — a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, ‘Here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow,’ and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives you your own impression of the scene before you.”

I believe that Monet also inserted colors he did not see. (Is it a sacrilege to say that?) Yet the end result was an overall effect that did capture an authentic impression of the light.

Stage 2: Modifying the colors we see

In Stage 2 we begin to metamorphose into true colorists. We realize that painting representationally is not just about trying to paint the colors we see; it is also about altering and interpreting those colors. However, our ability to appropriately modify the colors is based upon our fluency with observational color. How will I know which colors need to be altered if I’m not evaluating them correctly? If I can’t read values well, I may not recognize that one needs to be darker or lighter?

Mitchell Albala, Bagnoregio Under an Antique Light I, 2018, oil on paper, 7 x 9

In my own painting I find a great deal of information and inspiration from direct observation, but I also know that I have to modify the colors I see if I am to achieve the effects I want. In Bagnoregio (above), my goal was to make the hilltop town glow. I maintained the broad color assignments found in the actual subject — the hilltop town is an earthy gold tone and the distant hills are bluish. But I also lightened the values considerably, and heightened the color saturation. By being able to read values well and understanding how value affects color identity, I can make more informed color choices when I depart from observational color.

Stage 3: Intuitive color

Inevitably, as we get better and better at modifying and altering colors as needed, we reach a place where our choices start to become more intuitive. When does this transition begin? I’m placing it in Stage 3, but in fact it asserts itself in every stage of our development. It would be almost impossible for it not to. After all, color is the most emotionally-based and expressive aspect of the painter’s practice.

Scott Gellatly, Preserving Twilight, oil on panel, 18 x 18. Scott Gellatly is a painter whose years of experience painting from life have given him the ability to make intuitive leaps with his color choices. “Landscape painting is a combination of what we take in from our surroundings and what we bring to it,” says Scott. “This latter part allows for a greater inventiveness with color and to fully realize our response with the natural world.” See more of Scott’s work.

Scott Gellatly, Preserving Twilight, oil on panel, 18 x 18. Scott Gellatly is a painter whose years of experience painting from life have given him the ability to make intuitive leaps with his color choices. “Landscape painting is a combination of what we take in from our surroundings and what we bring to it,” says Scott. “This latter part allows for a greater inventiveness with color and to fully realize our response with the natural world.” See more of Scott’s work.

We can all aspire to operate from a more intuitive place, but it’s also important to remember that the more foundation we have with observational color, the better able we will be to make intuitive choices. In other words, an intuitive response to color is fueled by experience and knowledge.

1 Comment

Dear Mitchell, Excellent reflection about colour choices and I agree that the more we learn about colour the more we can be intuitive in it. I also have found nature to be the best teacher of colour and observing how it modify’s colour is a great example -such as in the changing seasons or even in a moment where bright light intensifies certain hues. It’s the way of the artists too, as is intuition. Happy Colours!