David Lidbetter, December Mist 1

In artistic composition, as in so many aspects of life, the differences are what make it interesting. There are many forces at work in composition. In my workshops I focus on movement, active negative space, simplified shapes, integration and unity, and of course variation — the key to dynamic and interesting compositions. Where we find variation, we find greater interest. When there is a lack of variation, the composition is static. As you’ll see, variation can occur in many different ways.

In this post, we’ll take a walk through the woods to discover the power of intervals and variation. Clusters of trees or forest scenes, with their crisp vertical trunks of varying weights, heights, colors and angles, offer a particularly clear illustration of intervals and variation.

T. Allen Lawson, Winter Interior, oil, 26 ×18

In this soft, quiet painting by T. Allen Lawson, we find both movement and stillness. It demonstrates all the aspects of variation that we will see at work in the progressive diagram below, and in the paintings at the end.

- Variation of the spaces between elements are called intervals; the “pacing and spacing” between the trees. ”In his book The Simple Secret to Better Painting, Greg Albert writes, “Never make any two intervals the same.”

- Visual weight or density is also a form of variation. This is found in the different thicknesses of the trees, and in their differences in color and value.

- Variation in the angles or direction of the trees.

On one level, Winter Interior is a complex piece. It has lots of detailed foliage and subtle shifts of value. But underneath it all is a simple pattern of varying intervals — and no two intervals are the same.

Building interest through intervals and variation

In this simple progression, the composition becomes progressively more interesting as different aspects of variation are added. Of course, these aspects of variation don’t apply only to forests and trees, but to virtually all kinds of compositions.

1. No variation. Fully static composition. All intervals are the same. The spaces in between the trees are the same, as are the widths, angles, lengths, and colors of the trees. Nicely symmetrical, but very static.

2. Varying the intervals. Interest increases slightly as the intervals between the trees are varied.

3. Variation in weight. In addition to variable intervals, there is variation in thickness of the trees.

4. Variation in directions/angles. Now we have variation in the intervals, the thickness of the trees, and their directions or angles.

5. Variation in color. Now we have variation in the intervals, thickness of the trees, direction or angles, and colors.

6. Variation in heights. Finally, we have variation of intervals, thickness of the trees, direction or angles, color, and height/lengths of the trees — creating the most varied and interesting “composition” in the set.

Intervals and variation in action

David Lidbetter, December Mist 1, oil on wood panel, 22 x 30. There is a lively dance among the trees in December Mist 1. This is the result of Lidbetter’s careful application of intervals and variation. Notice how the diagonal branches on the far left, upper right, and lower left create a delightful departure from the vertical trees we see elsewhere. We also find variation in the large “empty” negative space of the snowy foreground. It has an asymmetrical shape that moves in and around the trees, adding greater interest to the composition.

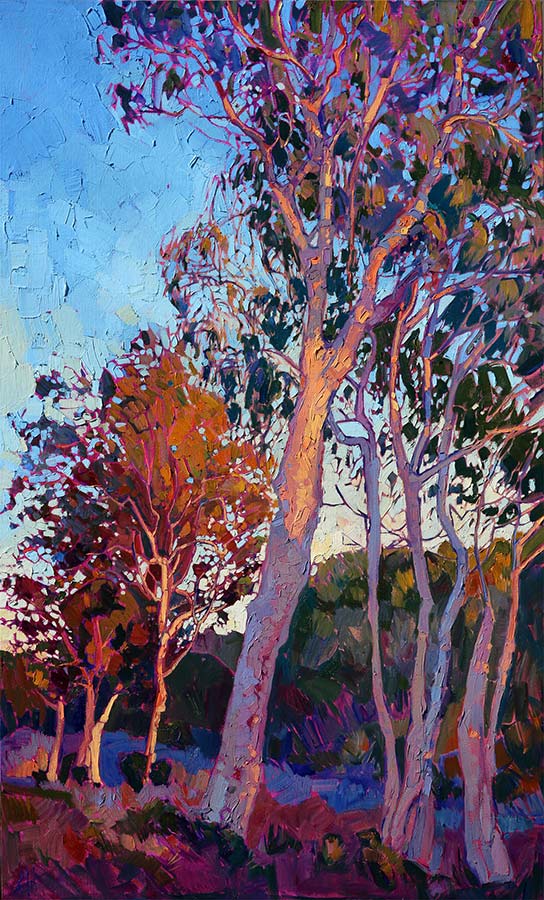

Erin Hansen, 2014, Eucalyptus in Color, oil on canvas, 30 x 50.

In this bold piece by Erin Hansen, the strong directional energy is owed largely to variation. Variation doesn’t only occur in the intervals between the tree trunks. We see a big difference in size of the red treetops in the lower left and large treetops in the upper right. We see variation in the height of the trees. And there is a large variation in the shape and size of the negative spaces. Compare the size and shape of the sky in the upper left with the much smaller “sky holes” in between the trees on the right. Wherever we look, we find no two intervals to be the same. All these variations create a tension that adds interest to the painting.

Mitchell Albala. Forest Through the Trees, 2016, oil on panel, 16 x 32. In this piece, the greatest variation occurs in a metaphorical sense: the stark difference between the light (day) and dark (night) halves of the painting. In addition to the varying intervals between the tree trunks, there is an asymmetrical shape to the foreground snow as it moves in and around the base of the trees.

8 Comments

Thanks. Great explanation of variation and composition. The six examples are simple yet effective.

Hi Mitch,

This is a wonderful blog post tutorial. I am looking forward to, or hoping for, another book from you.

Sincerely,

Sue Marquez

Santa Fe, NM

Very nice discussion Mitch.

I love, LOVE Erin Hanson’s paintings. She has the vibrant fury of van Gogh and the underlying depth and calm beauty of Monet. She is a master. I look at her paintings and I see how I feel about the wild spaces, the open spaces, the national wild lands.

Beautiful lessons … thanks a lot! Rosanna (Italy)

Lovely clear instruction, Mitch. As always!

Great post, Mitchell.

Dan Knepper

Good examples and explanation, Mitch. A question — will you be teaching a workshop or class on abstracting?