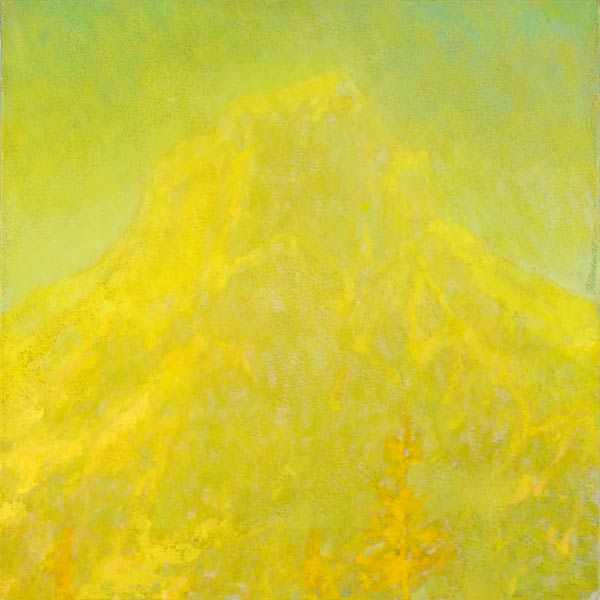

Ascension, Winter, oil on panel, 18 x 18 inches. $1,800 USD.

“Sunlight & Snow”

on exhibit at Red Sky Gallery, June 1–30, 2022

Snow covered mountains are the subject in each of the paintings in my Sunlight & Snow series. But from an artist’s perspective, the paintings are explorations of light, color, and atmosphere. In this post, I’ll examine three paintings from the series to show how each of these aesthetics plays out.

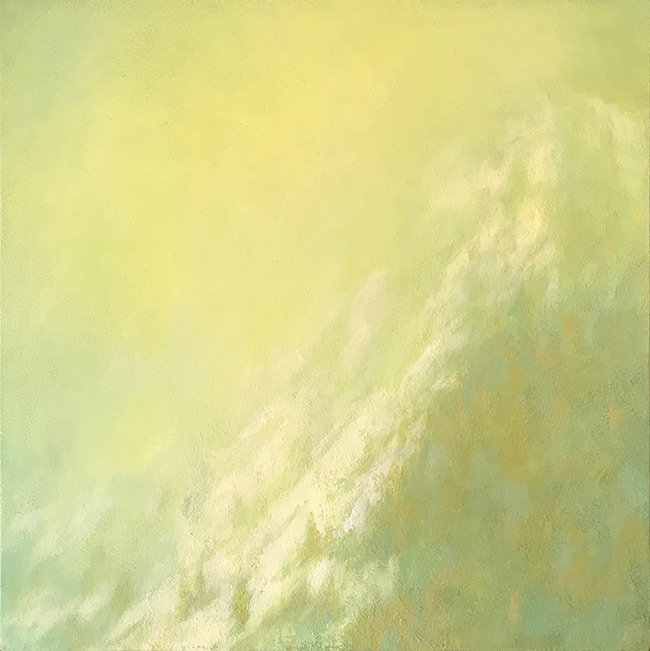

Border Peak in Sunlight – Pure Color as Light

Conveying a sense of light is perhaps the most important goal the landscape painter sets for himself. In the synthetic two dimensional world of a painting, the illusion of light is governed by two factors. The first is value contrast. Light versus dark. We live in a world of contrasts. Strong value contrasts in a painting connote light, just as they do in nature. As effective as value contrasts are, however, we don’t see the world in black and white. The second factor used to create an illusion of light is color. Our perception of light, in both the natural world and in painting, is very much bound to color. Color in painting can serve as a stand-in for natural light, which is exactly what we see in Border Peak in Sunlight.

Border Peak in Sunlight, oil on panel, 12 x 12 inches. $1,400 USD.

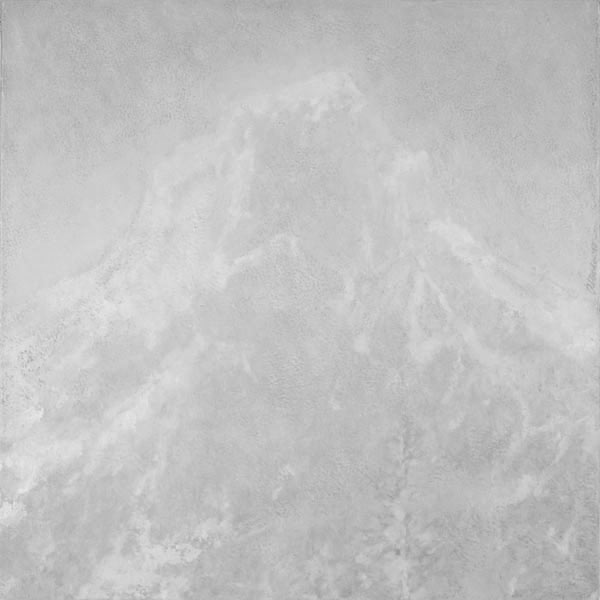

Border Peak glows. It is a deeply colored painting that is more about the light on the mountain than the mountain itself. To suggest light, painters rely on a combination of value contrasts and color. In Border Peak, I altered the dynamics of that formula. Strong value contrasts are replaced with color contrasts. In the black and white version of the painting (below), with the colors stripped out, we see that the value contrasts are minimal. Bright, saturated colors with subtle temperature differences do 95% percent of the work of suggesting light. This approach is essentially an an Impressionist strategy taken to the extreme.

Also see The Affect of Value on Color Identity in Impressionist Painting.

Ascension, Winter

Contrasts of Value and Saturation

Ascension, Winter, oil on panel, 18 x 18 inches. $1,800 USD.

The strategy for depicting light in Ascension is quite different from that used in Border Peak. Value and color are both at play, but the value contrasts in Ascension are much wider. This goes a long way toward suggesting light, but value never works alone. Here, the more saturated pink-orange color on the left is contrasted against the less saturated “brown” colors in the lower right. When saturated colors are played against desaturated or neutral colors, the saturated colors will seem that much more intense. There’s also a subtle complementary reaction between the light pink-orange color and the pale lavender-blues in the shadows.

Snowy Ridge, Early Light

Atmosphere Through Reduced Tonal Range and Soft Edges

Snow Ridge, Early Light, oil on panel, 12 x 12 inches.

Snowy Ridge, Early Light is a deeply atmospheric painting. Light snow caps along the mountainside melt into a thick blanket of warm light that rises over the ridge. Atmosphere in painting is created with a combination of soft edges and a narrow value range. This formula is not just an aesthetic device. It’s what we seen in nature. If we analyze atmospheric subjects — fog, mist, aerial perspective — we find these same narrow values and softer edges.

Edges occur at the boundaries between elements, where one shape differentiates itself from another. The thicker or more dense the atmosphere, the softer the edge will be. In Snowy Ridge, there isn’t a sharp edge to be found. Along the mountain’s ridge, there are “lost” edges, places where the edges become so soft they merge into the sky.

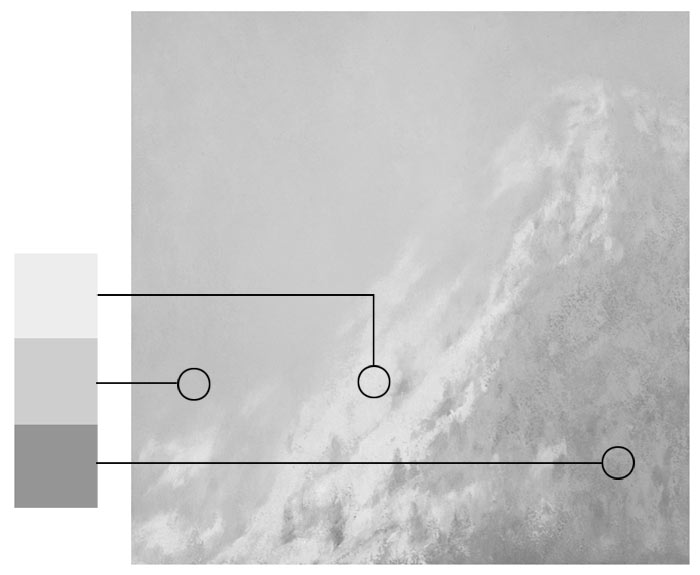

The full range of values available to the painter range from the lightest light (white) to the darkest dark (black). In an atmospheric painting like Snowy Ridge, that range becomes compressed. In the black and white version of the painting (below), the values are identified at the left. They are closely related, occupying just a narrow band within the potential range of values possible. Creating atmosphere with this narrow range of values is not an artificial construct; it works the same way in nature. When we perceive atmosphere in the form of aerial perspective, fog, or mist, we also see a reduced tonal range.

3 Comments

These paintings are really beautiful, Mitch.

They glow!

That’s the best compliment on can get on my paintings! I aim to glow!

That’s my purpose in life — to glow!