All subjects have a light source, but the source in the landscape — the illuminated dome of the sky — is part of the subject. This often leads the landscape painter to misread values and not establish enough contrast between the land and the sky, which is usually the biggest value contrast in a landscape. This, in turn, leads to an incorrect reading of the ground plane, which is often made too light. If these basic divisions get mixed up, it becomes very difficult to maintain a convincing sense of landscape space.

All subjects have a light source, but the source in the landscape — the illuminated dome of the sky — is part of the subject. This often leads the landscape painter to misread values and not establish enough contrast between the land and the sky, which is usually the biggest value contrast in a landscape. This, in turn, leads to an incorrect reading of the ground plane, which is often made too light. If these basic divisions get mixed up, it becomes very difficult to maintain a convincing sense of landscape space.

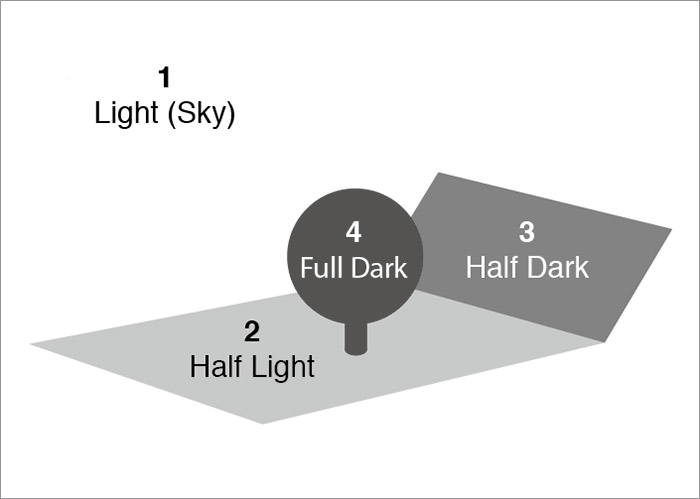

Landscape values are much easier to understand if they are viewed as falling into four major divisions or “value zones.” Robert F. Carlson in his classic “Guide to Landscape Painting” lays out his Theory of Angles. The theory essentially says that major landscape elements — skies, trees, hills, ground — are on different planes. The angle of the plane in relation to the sun determines how much light it receives, which in turn determines its value. For example, the sun and sky, being the source of the light, is almost always the lightest value. The ground, being directly under the sun, receives the most light (after the sky). Other areas, like trees and hills, which are more upright, receive less light.

Of course, these value divisions are not absolutes. There is some overlap between the divisions. For instance, there are times when the values of the ground compete with the value of the sky, as when the light side of a tree is the same value as the ground. There are also special conditions which defy the zones entirely: snow or desert scenes, in which the ground can be lighter in value than the sky; or the sun-struck side of a light-colored building. The point is that in knowing how the value divisions generally apply to the landscape, the value zones in any landscape can be correctly analyzed.

Value divisions in the landscape

Landscape values fall into four broad value divisions — light, half-light, half-dark, and full-dark. Although not absolute, these divisions are consistent enough to serve as a reliable guide to check value assignments at the start of a painting. There is also some overlap between the divisions, but the overall value of the sky remains lighter than the overall value of the land.

1 – LIGHT (sky) – The sky is almost always the lightest value zone in the landscape and accounts for what is usually the largest value contrast in the painting — between the sky and the land. This holds true even on cloudy or overcast days.

2 – HALF-LIGHT (horizontal planes) – The ground is a horizontal plane. Being directly under the sky, it receives more light than upright elements like trees and hills, but is still darker than the sky in the vast majority of circumstances. The exception might be snow or sandy beaches on a sunny day.

3 – HALF-DARK (slanting/sloping planes) – The next darkest zone is slanting planes, like hills. They receive less light than the ground, and are therefore darker than the ground, but lighter than more vertical elements.

4 – FULL-DARK (vertical planes) – Vertical elements, such as trees and architecture receive the least amount of light and so are usually the darkest values in the painting. Upright elements, of course, can be made up of two or more values, a light side and a shadow side. Depending on the local color of an element, its light side may be close in value to the slanting planes or the ground plane.

Additional Resources

Landscape Painting: Essential Concepts and Techniques for Plein Air and Studio Practice

Chapter 4, Value Relationships

The Lessons of Fog: Massing, Values Zones, Edges and Neutrals